PERMANENT EXHIBITION

This is a presentation of archaeological research in Eastern Crete since the late 19th century. Ancient writers often refer to Crete, which, in combination with the visible antiquities on the island, led here geographers, scientists and travelers as early as the 15th century. Foreign archaeological schools conducted the first investigations in Eastern Crete in the late 19th and early 20th century. To this day, in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lasithi, the British, French, Belgian, and American Archaeological School, the Irish Institute, as well as the Archaeological Society and Greek Universities, continue their research in Lasithi.

In this section, the science of Archaeology is presented in an understandable and comprehensible way. Archaeology brings to light,records and studies the remains of human activity to reconstruct and interpret the culture of past societies. The identification of archaeological sites is based on the analysis of historical sources, surface surveys, newer oral testimonies, and even random incidents. The excavations involve archaeologists, conservators, architects, topographers, designers, photographers and skilled workers. During the excavation, immovable and movable finds are revealed, which are conserved and stored. The process is completed byrecording, studying, publishing the material and presenting the finds in the museum exhibitions.

In this section, the science of Archaeology is presented in an understandable and comprehensible way. Archaeology brings to light,records and studies the remains of human activity to reconstruct and interpret the culture of past societies. The identification of archaeological sites is based on the analysis of historical sources, surface surveys, newer oral testimonies, and even random incidents. The excavations involve archaeologists, conservators, architects, topographers, designers, photographers and skilled workers. During the excavation, immovable and movable finds are revealed, which are conserved and stored. The process is completed byrecording, studying, publishing the material and presenting the finds in the museum exhibitions.

This section chronologically and thematically presents the course of Eastern Crete from the Neolithic Age to the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age. Although there is sporadic evidence of habitation in Crete since the Paleolithic period and in Eastern Crete from the Aceramic (new research in the Pelekita Cave) and the Middle Neolithic (steatopygic figurine from Kato Chorio, Ierapetra), the Late and Final Neolithic phases gave indisputable evidence for the existence of permanent settlements in the area. The processing and use of bronze at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC marks the introduction of the region into the Minoan civilization. Successively, the exhibition presents the first settlements, the old and new palaces of the area, the Neopalatial and Post-palatial settlements, the development of the bureaucratic system and administration, the intertemporal economic organization and production, the formation and consolidation of religious perceptions, the approach of death and burial practices, the image of the people of the Bronze Age.

This section refers to the identified sites from surface surveys and a few excavated onesdating to the Late and Final Neolithic Age, indicating the density of habitation in Eastern Crete. Apart from the general reference mainly with visual material in the identified sites, e.g., theNeolithic well at Fourni, surface surveys in Vrokastro, Isthmus of Ierapetra, Kavousi, etc., the Pelekita Cave, the House in Magasa, Azorias, Milatos and various sites in the area ofSiteia are presented with material remains.

In Eastern Crete, the first permanent settlements were established in the Late (5300-4500 BC) and Final Neolithic periods (4500-3200 BC). The use of caves could be for domestic use, as in the caves “Trapeza”, “Argoulia” and “Psychro” in the Lasithi Plateau, burial, as in “Theriospilio” of Pachia Ammos and “Skafidia” of the Lasithi Plateau, as well as domestic and at the same time religious use, as in “Pelekita” of Kato Zakros. Unique in Crete during the Neolithic period is the well at Kastelli in Fourni, which shows the ability to exploit underground water sources in an area with a dry climate.

Here is presented the largest residential pottery assemblage of the museum, deriving from the Early Minoan II settlement excavated at the top of the hill of MyrtosFournouKoryfi. In each of its six or seven consecutive houses, workplaces, kitchens, and warehouses with large pithoi were located, while one of the rooms was identified as a potter’s workshop. Large clay wine presses were used to produce wine; stone rubbers prove the cultivation of cereals, and a large number of loom weights indicate the occupation of weaving. In a small domestic shrine with three rooms, many vases were found, including the famous “Goddess of Myrtos”, a unique libation vase in the form of a woman. The settlement was abandoned after its destruction by fire at the end of the Early Minoan II period.

Prepalatial period

Prepalatial period

Prepalatial period

Prepalatial period

This section presents the palace of Zakros, at the easternmost tip of Crete, founded around 1900 BC and being rebuilt in ca. 1600 BC.Its location made it an important trade center with the East and a gateway to Crete for raw materials, artifacts and new ideas.Its architectural design is closely related to the other three palaces. The core of the complex was the central courtyard, from where a road leading to the port started. Around it, there are kitchens, workshops, warehouses, a treasury, an archive, a lustral basin, ritual and banquet halls and the so-called royal quarters. Its sudden destruction at the end of the Neopalatial period and the fact that it was never looted made it unique regarding the range and quantity of objects found in situ.

THE LIFE OF PEOPLE IN THE BRONZE AGE

In Malia lies the third largest Minoan Crete palace at the foot of Mount Selena. The most significant part of its remains visible today dates to the period 1650-1450 BC, while a small portion has been preserved from its initial construction phase (1900-1700 BC). The most important objects that came to light include the golden jewel of the bees, swords with handles made of crystal, ivory and gold, a stone scepter handle in the shape of a panther bust, etc., exhibited at the Museum of Heraklion.

Quarter Mu, Protopalatial period

Gournia provides a clear image of a small town of the Neopalatial period. Due to its central location on the isthmus, between the northern and southern coasts of the island, the settlement evolved into a rich economic center. The new settlement was reorganized after a disaster during the Old Palace period. It included a small “palace”–the center of the local administration – many houses, an organized road network and a rectangular public courtyard. At the end of the Neopalatial period, the city was destroyed, and in the Postpalatial period, there was a small-scale resettlement. The inhabitants were engaged in agriculture, livestock farming, fishing, pottery, metallurgy and textiles, while they had contacts with other areas inside and outside Crete.

THE LIFE OF PEOPLE IN THE BRONZE AGE

It is a building complex at Plakakia, Makrygialos, west of the modern settlement. It dates to ca. 1480-1425 BC.The building bears elements of palatial architecture. The movable finds include clay and stone vases, figurines and a steatite seal stone depicting a sacred ship, a priestess, and a palm tree. Its geographical location on the coast of the Libyan Sea and its remote from other Minoan settlements, combined with its architectural layout and the nature of the finds, indicate an establishment with an administrative and possibly religious character.

The settlement of Mochlos flourished thanks to its geographical location and the unique double harbor, which provided shelter in all weather. During the Prepalatial period, the settlement expanded along the coastal zone and a large cemetery was formed with graves-houses on the western slopes. The city was destroyed and rebuilt at the end of the Prepalatial and Protopalatial periods. It was destroyed again by the eruption of the volcano of Thera, rebuilt and then destroyed again around 1450 BC. In this period, the city had a center for holding festivals and 20-30 houses divided into four blocks. In the Postpalatial period, 13 much smaller houses were built on the ruins of the earlier city. The last phase of extensive habitation in Mochlos is represented by a fortified town with a port dating to the 2nd and 1st c. BC.

Neopalatial period

The Minoan settlement on the islet of Chrysi or Gaidouronisi, south of Ierapetra, is presented. The architectural remains revealed correspond to a small settlement with 10-12 houses, but with a highly flourishing economy that is attested by the unexpected quantity, but mainly the quality, of the movable objects that came to light, possibly related to the important role the island played as a purple processing center.

THE LIFE OF PEOPLE IN THE BRONZE AGE

The Minoan settlement of Sisi is located on the seaside hill, 4 km east of Malia, and occupies a strategic position. The site was inhabited from the PM IIA period to the advanced LM IIIb. The hill’s northern slope is occupied by a cemetery dating from PM IIA to MM IIB. Some large houses-workshops were discovered from the Neopalatial settlement, while an extensive complex organized in wings around an outdoor courtyard belongs to the last phase of the area’shabitation. A small sanctuary also dates from this period. An earthquake probably destroyed the complex during the late LM IIIBperiod, andwas not reoccupied.

Postpalatial period

The settlement of Chalasmenos, on the homonymous 240 mhigh hill, west of the mountains of Siteia to Ierapetra, is one of the most typical settlements of the LM IIIC period (12th c. BC), abandoned at its end and inhabited again in the Geometric period (8th BC). Its LM IIIC architecture combined Minoan and Mycenaean elements; its center was occupied by large rectangular buildings influenced by Mycenaean architectural types. At the northern end of the settlement was the public sanctuary.

Since the Neolithic era, artisanshave specialized in producing and distributing everyday objects (household vessels, tools, clothing) and products of social prestige (jewelry, seals, weapons). This section presents the primary production, with the cultivation of the land, the livestock breeding and often some industrial activities.

Prepalatial period

This section approaches the idea of agriculture. Fields are formed in valleys, plateaus and terraces on the slopes where cereals, legumes, olives, vines, flax and fruit are cultivated. At first, stone tools were used, then metal tools and the plough facilitated cultivation and increased production. Apart from their nutritional value, part of the agricultural goods also constitute the raw material for the industry and an item to be exchanged.

Livestock farming and beekeeping, two of the most important activities in Minoan Crete, are presented here. The finding of animal bones and teeth during the excavations of the Minoan settlements confirms the breeding of sheep and goats, pigs and cattle. At the same time,small buildings, interpreted as livestock facilities, have been locatedin mountainous areas. Regarding beekeeping, in the beginning, they collected honey from tree cavities and rock crevices, while later, they used clay beehives and smokers to improve production.

A separate section presents the importance of the sea for the Minoans. In coastal areas, they are fishing for small and large fish using hooks and nets, as testified by the finds. They also collected barnacles, oysters and crabs as food, purple for dye production, and conch shells to transfusion liquids and libations during religious rituals. At the same time, the finding of salt along with fish remains testifies to their preservation knowledge.

Neopalatial period

Here, we approach the activity of hunting, which has been a vital occupation since antiquity. Hunting in groups or alone seems to be an essential activity with prey hares, ibexes, deers, fallow deers, wild boars, wild cattle, badgers, and various bird species. In artistic representations, the dog is directly associated with hunting.

This section presents the pottery production. Pottery workshops have been located in palaces and settlements. At the same time, wandering specialized potters were manufacturing large storage vessels and larnakes in temporary facilities. After collecting and processing the clay, the potters made pots with or without a wheel and baked them in an open fire or a kiln. These are vases for domestic use, storage, transportation, and rituals, bearing engraving, relief, or painted decoration with geometric and stylized motifs but also with figurative themes from the natural and marine world.

Prepalatial period

Another important activity was manufacturing small and larger stone objects and vases. The craftsmen carve, using a variety of tools (knives, chisels, burins, drills, saws), hard (alabaster, rock crystal, marble, obsidian) and soft stones (chlorite, steatite, ophite) local and imported.

THE LIFE OF PEOPLE IN THE BRONZE AGE

Metalwork, one of the most important occupations of the Minoan artisans, is presented here. The raw materials are imported from Cyprus, Laurion, Cyclades, Asia Minor, Afghanistan and Egypt. After melting the metals in crucibles with the help of bellows, the craftsmen either forged them with an anvil and hammer to give them the desired shape or cast them into dies. They made vases, utensils, tools, figurines and knives. Bronze processing workshops have been located in Malia (Quartier M), Chrysokamino, Zakros, Palaikastro and Petras.

In the seal engraving workshops (as in Quartier M of Malia), the craftsmen used soft stones, bones or ivory that were cut with a saw to the desired shape and size, smoothed with scrapers and polishers, and then engraved the representation and smoothed the surface again. Later, processing semi-precious stones required greater skill andspecialized tools. The seals certified the ownership or authenticity of a product, while serving as jewelry or amulets.

Postpalatial period

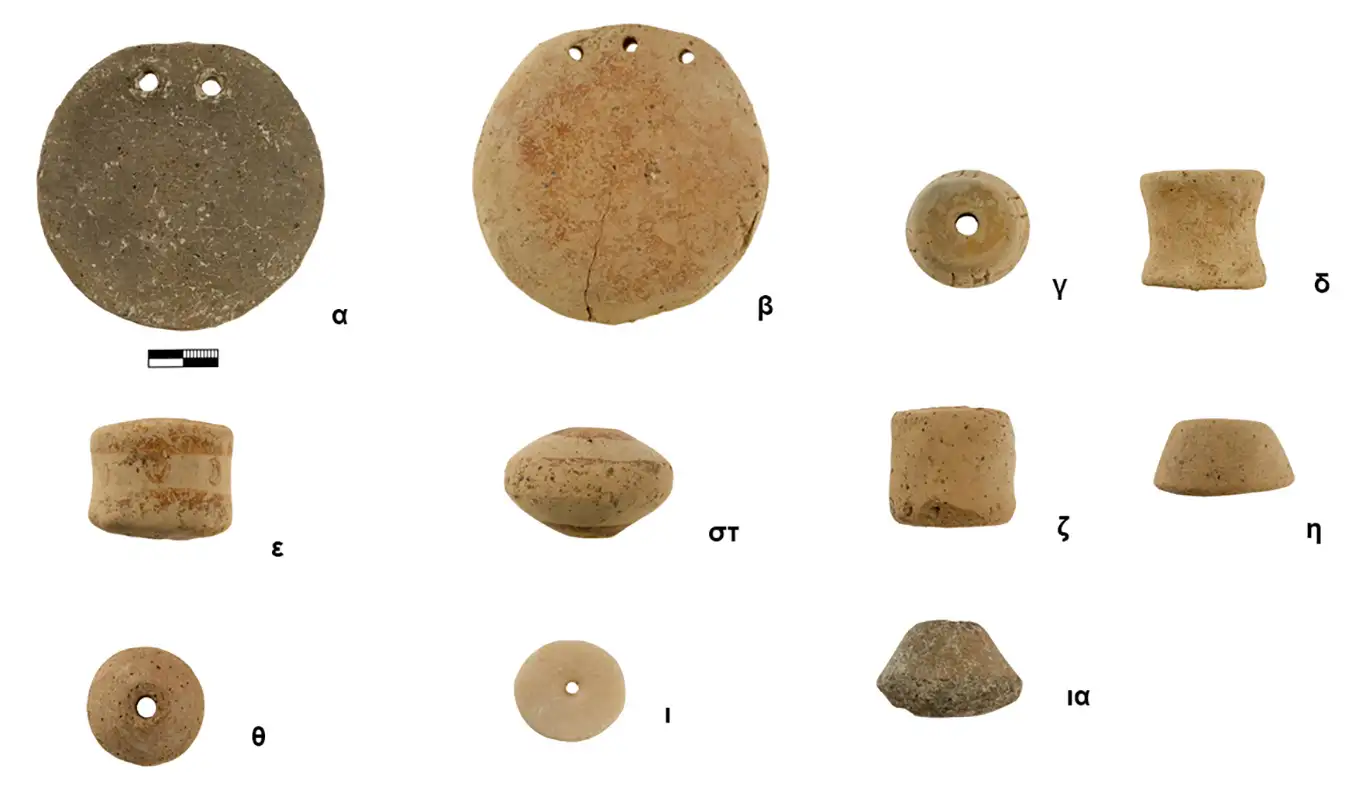

In the textile industry, an essential craft of the time, wool and flax were the primary raw materials. In the palatial workshops, weaving was taught, and part of the production constituted an export item. Numerous spindle whorls and loom weights from vertical looms were also found in many houses.

The region’s trade developed almost parallel with the primary and secondary production. With the presentation of imported objects from various areas of Crete or distant parts of the wider Eastern Mediterranean, as well as exhibits in which cultural influences are distinguished, an effort will be made to give visitors a clear picture of the circulation of goods and trade relations.

Quartier Nu, Postpalatial period

Neopalatial period

Neopalatial period

The importation into Eastern Crete already from the Final Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age of obsidian from Melos and Nisyros, ivory from Egypt and Syria, bronze from Cyprus and Laurion, tin and lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, and amber from the Baltic demonstrates the development of the trade outside Crete and the ever-increasing progress of navigation. In this section, the exhibits present the relations of the eastern part of Crete with distant areas, as well as the cultural influences traced through them.

Prepalatial period

Postpalatial Period

Postpalatial Period

This subsection presents products of various Cretan pottery workshops found in areas of Eastern Crete far from their place of production, thus testifying to relations and trade within the island and the circulation of goods from place to place. As an example, we mention the findings in the tombs of Agia Fotia, Siteia, vases from Central Crete, in the area of Malia, others made in the area of Merambelo, Messara or Southern Crete, or tombs in Eastern Crete of products of the Kydonia workshop.

Postpalatial period

THE LIFE OF PEOPLE IN THE BRONZE AGE

The section refers to worship and the interpretations given about it. The worship was initially performed in the open air, in caves and peak sanctuaries, while later, the domestic, palatial and public sanctuary was stabilized. In peak sanctuaries and caves, the faithful offered anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines, double axes, weapons and vases to the god.

Protopalatial period

Postpalatial period

In most of them, no architectural remains were found, except for some delimited by enclosures. The faithful brought offerings, which they either deposited in the crevices of the rocks or threw on fires lit during the rituals. The offers were mainly related to their health and activities. They offered anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines, vases and sacred symbols. Models in the form of parts of the human body, sometimes deformed, were dedicated as a request or appreciation for healing.

Protopalatial period

Protopalatial period

In private shrines, worship was practised in one of the house’s rooms. This had noparticular characteristicsexcept for a bench along a wall to support figurines and ritual vessels. On the other hand, the public sanctuaries were initially incorporated into the palatial complexes, which controlled, as it seems, the practice of worship.

Prepalatial period

Postpalatial period

Postpalatial period

This section presents the burial practices. A typical burial practice in Crete since the Neolithic and throughout the Minoan era was the inhumation, initially in caves and rock shelters, later in above-ground family tombs-houses, in trenches in pithoi and larnakes, and, finally, in tholos and chamber tombs. The earliest cremations in Crete, dating to the LM III A2 and LM III B periods, were discovered in Elounda,Eastern Crete.

This subsection refers to the characteristics of the particular architecture and thewealth of finds in the Prepalatial and Protopalatial periods’ tombs-houseslocated in Eastern Crete, which correspond to the large tholos tombs of Central Crete.

This section presents the caves and rock shelters, which, in addition to their use as burial sites, were also used for secondary burial, i.e. as ossuaries. Such places have been located at Petras inSiteia, Evraiki in Kavousi, and Agios Charalambos in theLasithi Plateau.

Prepalatial-Protopalatial period

In this section, the built tholos and chamber tombs of Eastern Crete will be presented, starting from the most important one due to the relations with the Cyclades and the largest cemetery of the Prepalatial period, that of Agia Fotia, with the majority of its 263 graves belonging to the category of small built tholos tombs. The built tholos tombs of the Postpalatial period discovered in Kritsa, Kaminaki, Kalamafka, Karfi and other sites, as well as the chamber tombs carved into the soft bedrock, including those of Gra Lygia and Myrsini, will also be presented.

THE LIFE OF PEOPLE IN THE BRONZE AGE

Burials and honors for the dead

Apart from the funerary buildings used for the burial of many family or clan members, there were also independent burials in pit trenches, cist graves or pithoi. A popular practice since the Middle Minoan period was the burial of the dead in pithoi in a contracted position. Large cemeteries with pithos burials were investigated in Pachia Ammos and Gournia. This practice continued in the Post-palatial period, with infants and children buried in small pithoi or other storage vases. Typical is the pithos burial from Krya, Siteia.

The section gives information about the external appearance of the Minoans, deriving mainly from wall paintings, figurines found on peak sanctuaries, seals, as well as jewelry and objects related to the care and grooming of the body.

This era took its name from the generalization of using iron as a material for manufacturing tools and weapons. Settlements of the Early Iron Age (970-810 BC), mountainous and lowland, are built on sites where Minoan settlements existed before. The unrest caused by the armed claim of the island’s arable land forced the Cretans to move to mountainous and barren places (settlements – shelters). Worship continues to be practised in domestic or outdoor sanctuaries, in caves, while the first temples appear. In the 7th century, the aristocratic families seized power, and the aristocratic system of governance was maintained until the Hellenistic era. The transition from the komai (villages) to the cities took place gradually, while preserving the Archaic composition of the settlements and the traditional forms in architecture is evident.Conservatism and lack of renewal also affect the artistic creation that follows the Greek standards. On cultural stagnation since the 5th century BC onwards, the long and cruel civil wars between the Cretan cities are also responsible. Crete acquired a key strategic position in the new political-geographical unity created by Alexander’s conquests. From the 2nd century BC, it became a base for pirates who attacked ships and Roman ports. In 67 BC, the Romans occupied the island, which becamevery prosperous as part of the Roman Empire.

There is little information about the first centuries of the so-called historical period (1050-630 BC). We can only indirectly detect the most critical developments on the island, such as the arrival of new population groups and the change in the administrative organization. It seems, however, that in Eastern Crete, there were no dramatic changes at the end of the Bronze Age. Still, initially, the Cretan-Mecenean tradition continued to a large extent, as at least the evolution of the structure of the settlements and the elements of religion and worship practice indicate. During this period, however, the institution of the Greek city-state with the urban center and the territorial area, the “chora”, would prevail throughout Greece and Crete for many centuries and until the Roman imperial period. The movement and unification of settlements and the creation of urban centers are considered to have occurred in the 8th century BC. Apart from the references in epigraphic and literary sources, a fundamental prerequisite for the characterization of a city as an independent state is the sovereignty of its territory, the existence of legislation and political institutions, a separate foreign policy, the ability to administer justice, the maintenance of the army, the issuing of coins, the imposition of duties and the management of its revenues.

The Late Minoan settlement (1200-1025 BC) in Kastrowas succeeded by the enlarged Protogeometric settlement (1025-850 BC), which partially changed its form in the 8th c. BC. The settlement rooms include permanent residential facilities, while the finds provide information about the daily life of the residents and their relations with the natural environment and the utilization of its resources. The size of the settlement decreased during the 7th century BC, which was abandoned in the end.

This section aims to give a brief picture of an Archaic settlement with its social, political and economic activities. Azorias is the only excavated site in Crete of urban character of the 6th century BC with finds and architectural remains that provide unique insights into the transition from the Early Iron Age settlement to the Archaic city-state, into the political economy of an early Greek city, and the changes in social, economic, and political organization during the late Archaic period.

EASTERN CRETE FROM THE EARLY IRON AGE TO THE LATE ANTIQUITY

This section presents the importance of religion and the evolutionary course of religious perceptions and practice in the lives of the Cretans of Eastern Crete during early historical times. The sanctuaries within settlements, over time, acquire independence and function as places to exercise rituals andcontribute to strengthening the community’s cohesive bonds. On the other hand, the sanctuaries in the countryside attract not only the inhabitants of the area but often from other neighboring. Although it is usually challenging to identify the worshipped deity, the votive offerings reveal the era’s complex religious and social changes.

Sklavoi, Archaic period

The Museum collection hosts a few finds from the Cave of Psychro, known as the Diktaion Andron since many are distributed in various other museums, most of which are in the Museum of Heraklion. It is presented in this subsection because it is one of the most important and imposing worship caves of Crete, covering an extremely long period, from the Middle Minoan to the Archaic era, i.e. from 1800 BC to ca. the 7th century BC, except a few finds dating to the Medieval period, one of the most important places of worship on the island. Here were found bronze figurines of men and women representing the faithful in characteristic worship positions, animal figurines substituting the real ones, bronze tools, knives, axes, razors, blades, seals and fibulae, which will be presented with rich visual material.

The first-millennium cemeteries are still outside the settlements, often in places where Minoan tombs existed, many of which were reused. The construction of tholos and chamber tombs ceased in the 8th century, but their use continued in the 6th century BC. In Crete, burials and cremations coexist in the same tomb until the 9th century BC. Gradually, the area of the family graves narrows, and the new dead are placed in the place of older burials that are removed. The first major change in burial customs occurred in the 7th century due to substantial social changes that allowed citizens to realize their contribution to society. It is then that the first individual graves appear in Crete. The grave goods are included among the deceased’s personal belongings, and their number gradually increased from the 11th to the 7th century, thus indicating the corresponding economic growth of the island’s inhabitants.

EASTERN CRETE FROM THE EARLY IRON AGE TO THE LATE ANTIQUITY

From the Archaic period onwards, the organization of Cretan citieswas gradually consolidated based on the known system of the city-state from the rest of Greece. The prominent city-states of Eastern Crete were Hierapytna, Itanos, Praisos, Lato, Olous, Istron, Dreros and Malla. These cities bring together the basic properties of a city-state. They cover a specific territorial area consisting of the town and the countryside, and borders are strictly defined, often with special treaties in case of conflict, such as those of the Latians with the Oloundians and the Hierapytnians. Their characteristics are independence and autonomous operation at all levels, political, administrative, religious, and economic, as well as that each one passes its laws and has its own patron gods, calendar, celebrations and, of course, coins. Over time, some cities are abandoned, others peacefully, such as Lato, and others violently after destruction, such as Dreros and Praisos. The cities constantly evolved within a complex network of intra-Cretan and extra-Cretan relations until the Roman conquest, when their status changed radically with the assimilation into the new political reality as a minimal part of a vast centralized empire.

Hellenistic period (220-216 BC)

The excavation brought to light an important part of the ancient city of the Latians with its political-religious center, public buildings and part of private residences. The stele found in the central reservoir of the city, bearing the text of the Treaty of the Latians with the Gortynians, confirmed its location and name. At the end of the 2nd century BC, the center of gravity was shifted to the Kamara coast, which flourished during the Roman imperial period. Its remains have been uncovered beneath the modern city. The occupation of Istron and the dispute with Olous over the border sanctuary of Aphrodite/Ares are important events in the history of Lato-Kamara. Inscriptions and other finds indicate relations with cities inside and outside Crete (Dodecanese, Asia Minor).

Hellenistic period

Residential remains on the broader area date to the end of the Final Neolithic period. The urban center of the territory of the Istronians during the Hellenistic period is located on the Nisi peninsula near the settlement of Kalo Chorio. The domain of the Istronianscan only be roughly determined from the archaeological remains, which must have included the wider area around the settlement of Kalo Chorio, while the cemetery of the city has been located at Katevati. Epigraphic evidence confirms the relations of the Istronians with cities of the islands (Tenos, Kos) and Asia Minor (Teos, Miletus, Pergamon). After 183 BC, neighboring Lato occupied Istron, which has since ceased to exist as an independent city-state.

Hellenistic period

The visible ancient walls in the sea on either side of the isthmus of Poros, the discovery in 1898 of a stone stele with various decrees of the Oloundians and later public documents and decrees for treaties with the Rhodians and the Lyttians, as well as the limited trial trenches at Exo Poros identified the location of the urban center of the Oloundians’ territory. The city cemetery is located in the settlement of Schisma and has been extensively researched. The city’s prosperity continued during the Roman imperial period, as evidenced by epigraphic testimonies and excavation finds.

Hellenistic period, (205/4 B.C.)

The urban center of the territory of the Drerians is located on two hills northwest of modern Neapolis. The habitation in the area dates to the Sub-Minoan times (1050-900 BC), but the distinct urban planning began in the 8th century BC. Remains of houses and parts of fortification walls of various periods, public buildings in the agora area (prytaneion, cistern), as well as sanctuaries in the agora and on the acropoleis can be seen from the “asty” (town). The city’s Geometric cemetery is located north of the first hill. Inscriptions of Archaic (legislative, Eteocretan, etc.) and Hellenistic times (most important, the oath of the Drerians) have been found in various parts of the city.

The “city” of Hierapytna is located west of modern Ierapetra, while in its territory belonged the Roman settlement in Myrtos. The key location favoring contacts within and outside Crete and the development of diplomatic and military activity gave Hellenistic Hierapytna a dominant position in Eastern Crete. It was the second most important city on the island during the Roman imperial period after Gortyna. Hierapytna conquered and destroyed Praisos in 145 BC, thus acquiring a common border with Itanos. This led to long-standing border disputes resolved by the arbitration of Magnesia of Asia Minor and Rome.

Praisos is located on three hills in the center of Eastern Crete near modern Nea Praisos. The habitation in the area dates to the 8th century BC, as evidenced by the very important sanctuaries and sanctuary deposits unearthed on the acropoleis A and C and in regional sites. The city is considered the center of Eteocretans, indigenous inhabitants of Crete, an element that gave it a particular character, traceable in the material remains, primarily the so-called Eteocretan inscriptions. The modern history of Praisos is characterized by the continuous conflicts with the neighboring Hierapytna and Itanos and especially the tragic end of its existence, written in 145 BC, with its destruction by the Hierapytnians.

Hellenistic period

Roman period

The easternmost part of Crete was part of the territory of Itanos, the urban center located on two hills southwest of Cape Samonio. In the “asty”, remains of houses, a temple and fortification walls were found, while in the wider area, the existence of sanctuaries, was ascertained. The relations of Itanos with the Ptolemies and the invitation of the Egyptian garrison, as well as the dispute with Hierapytna over the sanctuary of Zeus Diktaios and the islet of Lefki (Koufonisi), finally resolved in favor of the Itanians, are milestones in the history of the city. On Lefki, a center of purple production, very important buildings have been discovered (temple, theater, baths, aqueduct), which led to its characterization as “Delos of the Libyan Sea”.

This section presents the agricultural and livestock production that was a cornerstone of the island’s economy, as in previous periods. On the other hand, industrial production has been relatively limited. Both, however, essentially covered the needs of the island’s inhabitants. Trade, especially transit trade, developed mainly from the 4th century BC. At the same time, mercenary work and piracy were important sources of income in the Hellenistic period.

The main occupation of the Cretans was agriculture and livestock farming, the importance of which is evident from their frequent conflicts over the possession of areas suitable for agriculture and livestock farming. Other activities included the collection of the famous endemic herbs and aromatic plants, beekeeping, logging and fishing. The industry was relatively limited. Inscriptions refer to builders, scribes, kithara players and tanners, while archaeological evidence indicates industrial activities related to ceramics, weaponry, metalwork, stonework, basketry and weaving, salt collection, purple processing and yarn dyeing.

Archaic and Hellenistic periods

Archaic and Hellenistic periods

Industrial activities were mainly aimed at meeting domestic needs and rarely at export trade. These had to do with producing low-quality utilitarian pottery, lamps, figurines and bricks (ceramic kilns in Lato and Kalo Chorio) and extracting grindstone from Mount Oxas, Olous, and lead from Ziros, Siteia. Purple processing was developed in Koufonissi, manufacturing dyes for textiles, leather processing, salt collection in salt marshes and textile production, mainly to meet domestic needs.

Hellenistic period

Hellenistic period

The information we have on the circulation of goods during this period mainly constitutes archaeological research results. Besides wine, exports were limited and primarily concerned agricultural and livestock products, timber, honey, wax and grindstone. The imported products were more in quantity and value, such as good quality pottery, glass vases and marble architectural members, sarcophagi and sculptures from the Aegean islands, North Africa, Asia Minor and Italy

Classical period

In eastern Crete, the cities of Hierapytna, Itanos, Praisos, Lato, Olous and Malla began minting coins in the 4th century BC, with Hirapytna and Lato continuing for a while during the Roman imperial period. These coins seem to have local circulation, some even for a limited time. The coins of Hierapytna and Itanos constitute exceptions since they seem to have circulated outside their territory.The coins bear the issuing city’sname (e.g.Praision, Itanion, i.e. of the Praisians, Itanians etc.) and often the magistrate’sname. The depicted themes represented each city’s religious tradition and unique character. Thus, patron gods appear, such as Vritomartis on coins of Olous, Eileithyia of Lato, and Zeus of Malla, while the sea god Glaukos is chosen for the coin of the predominantly naval Itanos. The geographical location, as well as the intense commercial, political and military relations of the region with other cities of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Hellenistic kingdoms, as well as the occupation of the inhabitants with mercenary work, contributed to the increase after the 3rd c. and especially in the 2nd c. BC of foreign coincirculation, mainly of Rhodes, Knidos, Pergamon, Syria, and Ptolemaic Egypt. After the conquest of Crete by the Romans, coins from various mints of the Roman Empire circulated in the area.

The everyday life of the people of the time, men and women, was related to their position in the social hierarchy. Free citizens exercised, fought, participated in the city’s public life and exploited their property. The rest were engaged in manual work and other professions. Women were primarily occupied with home care and did not participate in public affairs. In the urban centers of Eastern Crete, most houses consisted of one to three rooms with a built-in hearth in one of them. Some houses of affluent citizens, however, show more elaborate construction. The usual equipment of the houses included mainly clay but also metal and stone utensils, wooden furniture and fabrics that served the everyday needs of the household and the home economy.

The structural materials of the houses of this era included local stone for the walls and wood and clay soil for the flat roofs, on which tiles were rarely used. The floors were covered with clay soil or were paved, while in the Roman period, they were decorated with mosaics (Ierapetra). The household effects included clay and stone vases, lamps, stone basins, rubbers, grinders, and stone or marble table legs. Most of the furniture seems to have been wooden, so they left no traces behind. Rare finds are the clay basin from Lato and the marble table support from Kamara (Agios Nikolaos). Weaving, known since the Minoan times, still occupies an essential place in the economy. The wool weaving was mainly done within the house to meet the household’s needs. For this purpose, vertical looms, numerous loom weights, spindle hooks, needles, and scissors were used.

Interest in the external appearance of the Cretans at this time seems to have been intense, as initially evidenced by the archaeological finds, mainly from graves, but also by human representations on vases and figurines. Male and female clothing reflects age, social status, financial status, occupation and the circumstances under which it is worn. A similar image is given by gold, silver, bronze or iron jewelry, with which women mainly adorn their heads, necks and hands. An integral part of the women’s appearance is theirextremely elaborate hairstyles and the use of cosmetics and perfumes, as evidenced by the number of objects related to body grooming.

Both written sources and archaeological finds testify to the intense engagementof the Cretans with sports. This is indicated by a large number of strigils (scrapers for cleansing the body) and aryballoi (small perfume containers) included as offerings in many male burials of the Roman cemetery of Agios Nikolaos, as well as the golden wreathed dead possibly identified with an athlete.

Objects identified with toys of the time are mainly found as grave goods in children’s burials and figurative representations on vases or figurines. These are miniature vases, carriages with wheels, dolls, spinning tops, clay figurines usually representinganimals (dolphins), glass pieces (for games like draughts), clay marbles and knuckle bones.

Religion, now closely linked to the administrative structures of the city-state and with a distinctive public character, plays a dominant role in people’s lives. At the same time, it constitutes an axis of organization of all aspects of public life. The gods are present in all important acts of the cities. They are mentioned in the decrees, seal alliances, give prestige to the coins, and fortify the borders. At the same time, they define and bless people’s time and activities. Worship has an evident public character without missing the indications for domestic–private worship. It is practised in temples, which are usually small in size, while at the same time, the use of outdoor sanctuaries and the timeless worship in sacred caves continues.

Archaic period

Archaic period

The cemeteries in Eastern Crete were located on the outskirts of cities, and most had a long period of use. More than one has been identified in some cities, such as Kamara and Hierapytna. The various types of graves (in Eastern Crete, simple pit, tiled, cist and vaulted graves have been found) were organized in clusters, probably related to the clans and families. This internal organization is sometimes stated architecturally with the creation of built enclosures, while in Olous, an external enclosure demarcated the entire cemetery. The orientation of the graves is not uniform. However, the frequent placement of the dead “looking” to the West probably reflects the perception that there were the houses of Hades. Each grave typically contained only one burial, with a few exceptions. The burial ritual included special ceremonies, as evidenced by relevant finds, while the dead were always accompanied by grave goods, i.e. items the relatives placed in the grave for their loved ones. Many offerings had a symbolic or magical-religious character.The grave’s location and the deceased’s identity were usually determined by a mark, i.e., an inscribed cut block or a grave stele, which rarely bore a relief representation.

The transfer of the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to Constantinople and the gradual predominance of Christianity marked the first Byzantine period. Written sources and archaeological evidence inform us that eastern Crete has five coastal cities:Olous, Kamara, Ierapydna, Siteia,Itanos, and other smaller settlements. Until the middle of the 7th AD, the island of Crete had a strategic position within the unified Mediterranean, as it was a reference point in the maritime routes to and from Africa and Asia. The prevalence of the new religion on the island is documented by the number of Christian churches erected during the First Byzantine period, especially during the 5th and 6th centuries AD. In eastern Crete, churches of this era are mainly located in ports (Elounda, Pseira, Mochlos, Siteia and Itanos). There is no doubt that Christian churches existed in the city of Ierapetra since the Diocese of Hierapypta was documented by written sources as early as the 4th century AD.